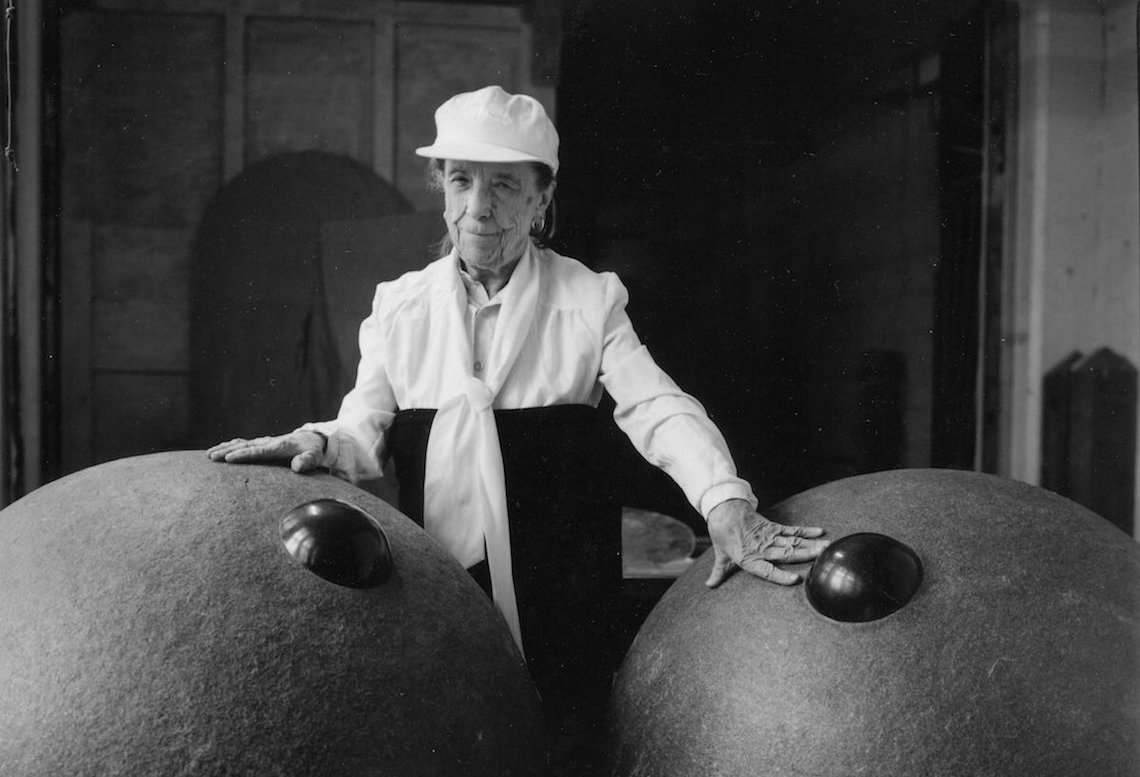

‘What is that even supposed to be?’ mutters a little boy as he surveys the work with youthful scepticism. It’s a typical British Tuesday morning and I am standing in the Artist Rooms at Tate Modern surrounded by a gaggle of school boys. I cannot help but smile at their mixture of enthusiasm, wonder and sheer confusion at the works of French artist Louise Bourgeois. It occurs to me in that instant how pleasantly surprising it is that these schoolkids are even in this place at this time. As my mind wanders back to the art, an elderly couple enter – they take one look at the stuffed amorphous form hanging from the ceiling, exclaim a slightly disgusted ‘oh no’ and promptly exit, presumably off to find a less offensive exhibition in their eyes.

Despite concerning two entirely opposite generations, both these anecdotes coloured my own experience of Bourgeois’ art in a way I could never have expected. The very concept of the Artist Rooms at the Tate stems from the desire to expose all audiences, particularly young ones, to great works of art. The accessibility of visual art, both practically and emotionally is of the utmost importance, far more important than any of us will ever know. By practical accessibility, I am referring to the financial and geographical factors that enable visual art to reach a range of different audiences and transcend any traditional categorisations of age, gender, ethnicity and wealth. In its very vision, mission and ethos, Tate Modern rises effectively to this challenge, providing opportunities to freely witness work that confronts contemporary questions and universal feelings of love, home, fear, sadness and death; feelings, in short, that make up emotional accessibility.

Practical and emotional accessibility marry together under the relevant themes that visual art conveys, particularly when these are the relatable sentiments and questions of 21st century society. Louise Bourgeois herself ties the two seemingly disparate wholes of practicality and emotion together in her own works, by using everyday materials such as stitched fabric or discarded clothes to reveal her inner psychological turmoil. By doing so, she renders the work even more accessible: its autobiographical nature immediately rings true with the viewer.

One of Louise Bourgeois’ greatest strengths is her ability to transform personal and psychological experiences into a universal visual language. Despite having previously argued that universality precedes emotional accessibility, it is important to note that the result is not necessarily easy to understand, or indeed, particularly aesthetically pleasing. Upon entering the Artist Rooms, it does not seem unnatural to feel distant from the old clothes on hangers, lumps of fabric hanging from the ceiling or the massive spiders. However, the beauty of Bourgeois’ art is that, by the time you leave the exhibition, you feel a personal connection with the tormented artist.

This brings me back to the confused little boy and the elderly couple. The reason that visual art holds so much weight and importance in the 21st century is that it enables the expression of universal emotions that so many often misunderstand or else shy away from. In the age of mental illness there is still a tendency to react negatively when an artist portrays and reveals their inner psyche, whether by acting shocked or by ridiculing or dismissing the work as weird or attention-seeking. We all claim to want better mental health services but, when it comes down to it, we act like talking about our emotions is offensive, or a taboo.

Understanding visual art is like reading a book – to be fully immersed, you must first enter the artist’s world. However, whereas in a novel the way in is through the first chapter, when it comes to art one must find their own first page. For me, it was through ‘Cell XIV (Portrait)’: a red three-headed statue sat in between bars. The sense of claustrophobia, inner torment and multiple psyches emitting from this sculpture spoke to me and I began to view the other works in a similar light.

Louise Bourgeois used her work as her own form of therapy and if we take the time to witness and comprehend it, it can enlighten us too. The art is there. The art is accessible. The rest is down to us. If we can open our eyes and learn to look – really look, not just see – then we can learn to understand and maybe, just maybe, learn to grow.

Interested in finding out more about Louise Bourgeois’ work? Follow the link below: https://www.tate.org.uk/visit/tate-modern/display/louise-bourgeois