Artistic expression has the power to take the world and its people into an era of progressive thought and action, but have recent changes put a damper on those efforts, or just fuelled the fire even more?

There has been a lot in the news lately. We are in an era of change. Change is good at most times, but not at the expense of others. That is what the changes we are facing at the moment are – unfair, inadequately planned and downright discriminatory. The majority of the world strongly disagrees – to put it nicely – with the inauguration of Donald Trump as President of the United States and the looming start to Brexit has left many people, businesses, traders and the entire younger generation fearing for their futures. With this, we have already experienced mounds of social, political and cultural turbulence, and its only been so many months since it has become official – the travel ban, alternative facts, the wall, wiretap allegations and the significant concerns amidst the triggering of Article 50 and the growing issue of the “broken health service” NHS, according to senior doctors.

These problems – most notably the Trump-related ones, to which this piece will be slanted towards – the world’s population are having to face are now even more prevalent in the underlying messages found in films. Films are made to express what the public is feeling, to educate them to the best of their ability, and possibly get the discussion going. But now, in this atmosphere where social, political and cultural representations hold a much greater power than just the telling of stories, this expression can grow into something much more prominent and necessary. And why is that? Because in this turbulent time, film can be so much more than a peek into the life of real and/or fictional people, more than an epic love story, or a comic duo causing mayhem, or chartering a supernatural force in the real world. Film has the ability to aid the equality and acceptance of all people, genders, voices, ethnicities, religions and sexualities.

It is artistic expression at its finest. Just look at how sales of George Orwell’s 1984 skyrocketed after Trump was elected, and on the 4th April, approximately 90 Independent theatres in America, and 1 in Canada screened the film adaptation in protest. A film that is over thirty years old can still make an impact now, what does that tell you about the power of the film medium, and what can it tell you about upcoming releases with similar storylines and themes? It tells us that even when the many changes being made covertly, or even overtly, attempt to pull the world back into a regressive time of discrimination and rejection, the underlying messages, morals and movements in film can fight against it to encourage an era of progressivism.

One example is Oscar Winner for Best Picture, Best Adapted Screenplay and Best Director, Moonlight, a story chartering the three stages of Chiron’s life, a young black man from Liberty City, Miami, on the wrong side of the tracks, not of his own choice, trying to make sense of it all. You sympathise with his yearning for a better life, you understand his confusion about his sexuality, his pain from having an unstable home life, but he finds himself, as a grown man, feeding into the stereotypes he tried to distance himself from – so what is the message? That you can never escape what society expects of you because of your skin colour or the neighbourhood you’re from, which is what we see in the final part of the film as a grown-up Chiron drives around town with a certain presence in the neighbourhood, stopping to do some business. Or is the film showing this to educate the wider world, the audiences going out to watch the movie, that these expectations, these stereotypes wired into our heads need to cease to exist as with them, progressivism is dying, the opportunity to give kids like Chiron a better chance at life and all it throws at you, the ability to choose their own path without hesitation, without fear.

A safe, welcoming place that they can call home, or where they can follow their dreams to fruition. The film doesn’t end with the image of a drug-dealing Chiron, no; it ends with him starting to feel safe in an environment where he can be open about his sexuality and where love is a possibility. Right now, in the aftermath of Trump does this place exist? Can a kid like Chiron go out and shout from the rooftops, in whichever corner of America, and/or the world, about who he really is? The film does express what is happening in the world, but it didn’t conceal the harsh truth of the world, the reality that discrimination, homophobia, minority typecasting, still make up the foundations of our society, and has crept out of the shadows in light of the burgeoning dent these events have formed.

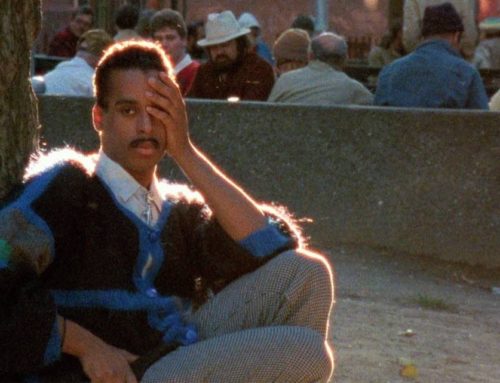

Get Out, directed by Jordan Peele, takes a different route of comedy horror/thriller to enlighten audiences about a major issue that identified the black community in America all those years ago, and from watching and understanding, you leave with the notion that maybe the issue never went away, not wholly anyway. Peele began writing the script in 2008, around the time when Obama was elected President, a time where the country first saw glimmers of a divide, a closeted one at that, but still it was there. And now that the film’s release coincided with a new presidency, one that has garnered a lot of hate and impeachment pleas, the film is a commentary on how a once united nation can fall into disrepute because a façade of liberalism is being picked at and turned on itself to reveal old prejudices still having a hold on some portions of the country. Get Out doesn’t shy away from including a number of deep symbolisms in the encapsulating of racial America and the troubling fears the black minority is yet to be rid of, for instance the police officer asking to see Chris’ ID despite not being the driver, or the subtle racism he endures at the hands of Rose’s family friends, like black being the new fashion.

There are little hints as well that make all the more sense once you have watched, understood and taken it all in, like Rose eating fruit loops and drinking milk separately as to not mix white and non-white things, or when Chris puts his hands up like a criminal when he hears police sirens, when in actual fact he is the victim. Society, as progressive as it seems, may not be so, with the example of news stories showing police brutality against black individuals constantly occurring, also alluded to in the film when Chris takes a photo of Logan on his camera phone, the mode in which we see the truths of these cases. By creating a film that so intricately addresses the issue of a racial America in the form of a horror/thriller, Peele thrusts the harsh realities shoved under the rug directly in his viewers’ faces, in the effort to enlighten them on the topic that is still circulating in the 21st century. Get Out is a strong example of using an artistic medium and voice to teach the world about an important subject, a subject that holds even more prominence during a time of uncertainty and division.

Moonlight and Get Out are praiseworthy pieces of cinema, films part of an undying breed that will continue to grace our news feeds and cinema screens, and epitomize vital subject matter and messages. But, there are other points of view taken by filmmakers to represent a need for progressivism. Based upon the non-fiction book of the same name, by Margot Lee Shetterly, Hidden Figures, directed by Theodore Melfi, takes a positive outlook in its portrayal of the black minority rising against racial stereotypes. Additionally, it is not just a socio-political message about ethnicity, but also gender, as the story of the hidden figures centres around three women, working behind the scenes at NASA, during the Space Race in the 1960s. The film ends with the message of striving ahead, destabilising the norm and outgrowing the stereotype you are taught by society to uphold – teaching little girls that they can make something of themselves, especially in a male-dominated workspace. The duration of the film alters the viewers’ spectrum of emotion, they are in and out of disgust at how these black women were treated – Dorothy having to run across campus to simply relieve herself in the “correct” bathroom – and there are heart-warming moments – Mary winning her case to study at a non-segregated high school in her journey to become the first female, black engineer.

And the majority white characters in the film extend these emotions to the audience, as a result of their acts towards equality, for instance, when Harrison knocked down the “whites only” sign above the bathroom. This film is an example of an ending to a story, the end of racial segregation, and the beginning of a new one, the start of equality, acceptance and a series of distinguished “firsts” held proudly by a community initially put down as never accomplishing such feats. It is a prime example of artistic expression educating society and community on what needs to continue in the country of America, especially in light of ignored hate crimes against the black community. And with this film in particular releasing in the wake of Trump’s comments about women, in light of the momentous Women’s March all over the world, and the most recent protest of the gender pay gap, the prevalence of gender inequalities is rife. The expression of women being just as strong, able, and deserving as men has been in the media for years, and with the arrival of Trump and his derogatory comments, the country has been unwillingly pulled away from the goal of equality. And with a film like Hidden Figures, and many more to come, along with other kinds of artistic expression, that goal can and will be strived for.

Sometimes the artistic expression works its magic, albeit through different methodology, even before the film releases, like Asghar Farhadi’s The Salesman, a story within a story drama about a husband trying to determine his wife’s attacker as she struggles to come to terms with the trauma itself. The story is about people dealing with a personal problem, overcoming trauma and finding justice. There is no political point of view, no connection to Trump and his Presidential seat, but it was willed so after the political move of the Travel Ban on the 26th of January 2017, blocking the entry of citizens from seven Muslim majority countries to the US, one being Iran, where Farhadi is from. He then boycotted the Oscar Ceremony in protest, condemning the ban and its subsequent politically motivated racial discrimination, where he won Best Foreign film for The Salesman.

In light of all this “buzz”, if you want to call it that, Farhadi expressed his disagreement with the ban, and it was indeed an artistic form of expression as, rather than proudly accepting his award, or celebrating his momentous win, he used the platform of the Oscars stage to voice his views on what happened through a speech read by Anousheh Ansari. The film itself didn’t suffer at the hands of this press, and why should it, its not bad press. He made a film about solidarity, justice and the strong bond of husband and wife in the face of trauma, taking inspiration from an American classic, Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman, and with the artistic expression of the actual film and its surrounding chatter, The Salesman will go down in history as aiding the progression of a society where gender equality, female rights and the welcoming of minority communities are encouraged and maintained.

Each of the films discussed share a common thread. They enlighten audiences on the whole-hearted embracing, acceptance and appreciation of difference – different people, genders, voices, cultures, communities, sexualities, and religions. This is the golden perspective that can bring together a community, a country and a world that has become divided, and the questions to leave readers with are – is it all because of film and its vast community of directors, writers, actors and so on? Can this artistic expression truly aid the progressivism of society and its people amidst the current political turbulence?

I believe it can, addressing the issue in this medium itself is one strand of expression already, and there are many more out there now and in the works to knock regression on its back.